Constellations of Words

Explore the etymology and symbolism of the constellations

the Bird of Paradise

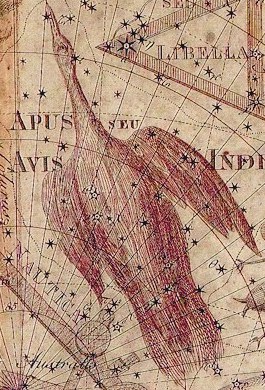

Johann Bode,Uranographia, 1801

Contents:

1. Clues to the meaning of this celestial feature

2. The fixed stars in this constellation

3. History_of_the_constellation

Clues to the meaning of this celestial feature

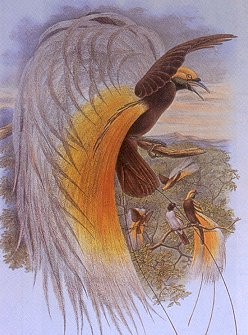

John Gould prints fromMonograph of the Birds of Paradise

This constellation, Apus, refers to the Bird of Paradise, from the family Paradisaeidae, native to New Guinea and adjacent islands. The name apus literally means ‘without foot’, a-, ‘without’, + –pus, ‘foot’.

There is also a bird genus Apus comprising the family Apodidae (apodes is the plural of apus), commonly known as swifts, the Common Swift is Apus apus

The Greater Bird of Paradise is Paradisaea apoda, ‘legless bird of paradise‘. This species was described from specimens brought back to Europe from trading expeditions which been prepared by native traders by removing their wings and feet so that they might be used as decorations. This was not known to the explorers and led to the belief that these birds were beautiful visitors from Paradise that floated in the air and never touched the earth until death [].

The male birds of paradise are richly colored with flamboyant feathers while the females in comparison are rather dull and inconspicuous. The king bird of paradise is Cincinnurus regius, Latin cincinnatus or cincinnus, ‘curly’, + –urus, ‘tail’. There is also Magnificent Bird-of-paradise, (Cicinnurus magnificus), and Wilson’s Bird-of-paradise, (Cicinnurus respublica). There was a temporary Roman dictator, Lucius Quinctius Cincinnatus (519 BC – 430 BC?), of whom Cincinnati in Ohio was named.

The birds were believed to be from Paradise. Paradise is an English word from Persian roots. Paradise is generally identified with the Garden of Eden or with Heaven. These birds might represent angels from heaven which are portrayed with wings? An angel is understood to be a celestial being that acts as an intermediary between heaven and earth and are depicted hovering in the air. The Portuguese traders to the Moluccas (Maluku) Islands were the first to encounter the birds of Paradise. The name Maluku is thought to have been derived from the Arab trader’s term for the region, it is from an Arabic word, malik, meaning ‘king’. The related Hebrew word mal’ach (malak) is the Biblical word for angel [], the word also meaning ‘messenger’. “Malachi was the last of the minor prophets and God’s last inspired messenger” []. “The hula dance is remarkably like the bird of paradise dance and is celebrated on the Hawaiian island of Molokai” [].

] A photo of life-mount specimen of Wilson’s Bird-of-Paradise from American Museum of Natural History, New York]

The birds of paradise live in rainforests and have a lek-type mating system, in which twelve to twenty male birds gather together to dance on huge trees in the forest, which have wide-spreading branches and large but scattered leaves, giving a clear space for the birds to display themselves and exhibit their plumes. They raise up their wings, stretch out their necks and elevate their exquisite plumes, keeping them in a continual vibration. Females visit the lek and wander among the displaying males as if comparing their virtues, or ‘window shop’ for the best suitor. If a female does not find a male she likes, she moves on to another display area, usually selecting the most eligible male, or the most gaudy male. From the lek the males coo and whistle at passing females. Usually only a few males out of all those present on the lek ever successfully mate [, 10].

These birds were believed to be from Paradise, called Manucaudiata, or Manuqdewata (bird of the gods) were said to always fly; they would never touch the ground. They would fly with their faces towards the sun, until they died. The female would lay her eggs on the male’s back, and hatch them as he flew. Some versions said they lived on air, others said they lived on dew and the nectar of spice trees. [11

The above description of the Birds of Paradise could be more true for the swifts (Apus), the Common Swift is Apus apus. Swifts have such small legs that they were believed to have none at all [12]. They are the most aerial of birds, and drink, bathe, preen, collect food and nesting material, all without alighting, some even sleep and mate on the wing. Swifts are swift: they fly very fast. The word swift comes from the Indo-European root *swei ‘To bend, turn’. Derivatives: swoop (from Old English swapan, to sweep, drive, swing), swift (from Old English swift, swift, quick < ‘turning quickly’), swivel (from Middle English swyvel, a swivel). Possibly Germanic *swih-; switch (from Middle Dutch swijch, bough, twig), swap (from Middle English swappen, to splash, from a source akin to German schwappen, to flap, splash), swive (to have sexual intercourse), sweep (Birds of Paradise sweep aside leaves of the display area). [Pokorny swe).- 1041. Watkins].

The flower called ‘bird of paradise‘ is of the genus Strelitzia (after Mecklenburg-Strelitz). “In Russian ‘Swift‘ is strizh, is suggestively similar to the Latin strix (genitive strigis), which means both ‘screech-owl’ and ‘witch’ and is related to the Greek verb ‘(s)trizo‘, which means “to screech, squeak” of animals and ghosts. Swifts too have been associated with the supernatural, perhaps because of their black plumage, their cries, and some of their more unusual habits, like ascending into the sky at dusk and never landing except to breed. These supernatural associations may explain some older words used for Swifts in English: devil-bird, deviling, swingdevil (swing devil), devil’s screecher, and devil swallow” [13]. These words come from the Indo-European root *trei– ‘To hiss, buzz’. Derivatives: strident (from Latin stridere, to make a harsh sound), trismos (from Greek trismos, trigmos, a grinding, scream). [Pokorny 3. streig-, 1036. Watkins] Owls are of the order Strigiformes– Family Strigidae. A strigil was a small, curved, metal tool used in ancient Greece and Rome to scrape dirt and sweat from the body [14].

Martlet AHD

The swift, Apus apus, has been given amazingly sticky saliva. Outside the body, it acts like a fast-drying glue [15]. Some species of swift, the cave swifts, use only saliva to build their nests, these nests are the basis for bird’s nest soup. Other swifts build their nests from other materials, this is caught in the air, and glued onto the nest with saliva, they attach the nest to vertical walls or other surfaces using saliva as glue.

“The tradition of depicting swifts without feet continued into the Middle Ages, as seen in the heraldic martlet. A martlet (derived from from the French word for swift, martinet, ‘martin‘) is a mythical bird often used in heraldry. The inability of the martlet to land is often seen to symbolize the constant quest for knowledge and learning. It has been suggested that this same restlessness is the reason for the use of the martlet in English heraldry as the cadency mark of the fourth son. As the fourth son received no part of the family wealth and had to earn his own, the martlet was also a symbol of hard work, perseverance, and a nomadic household”. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Martlet

© Anne Wright 2008.

| Fixed stars in Apus | |||||||

| Star | 1900 | 2000 | R A | Decl 2000 | Lat | Mag | Sp |

| alpha [α] | 14SAG03 | 15SAG26 | 14h 47m 51.06s | −79° 02′ 41″ | -58 13 41 | 3.81 | K5 |

| gamma [γ] | 21SAG19 | 22SAG42 | 16h 33m 27.46s | −78° 53′ 50″ | -55 59 56 | 3.90 | K0 |

| beta [β] | 21SAG34 | 22SAG57 | 16h 43m 04.6s | −77° 31′ 3″ | -54 32 13 | 4.16 | G8 |

History of the constellation

from Star Names, 1889, Richard H. Allen

The constellation Apus, the Bird of Paradise, was created in 1604, or Apous, as Caesius wrote it from the Greek, lies immediately below the Southern Triangle, about 13° from the South pole. It is the French OiseaudeParadis; the German ParadiesVogel; and the Italian UccelloParadiso

Its avian original is found only in the Papuan Islands, and the title is from apous, Without Feet, for the ancient Greek swallow [The Common Swift is Apus apus], but well applied to this bird that has been thus fabled, as witness Keats’ “legless birds of paradise,” in his EveofSaintMark

Bayer strangely had it ApisIndica on his planisphere of the new southern figures, where the typical bird is shown, as also in the corresponding page of text; but the universal consent as to the name Apus, or Avis, and its appearance as ApusIndica and IndianischerVogel in the abridged German edition of Bayer’s work issued in 1720, with the fact that he had another, and correct, Apis, would indicate a typographical and engraver’s error in the original; but I have not seen this alluded to till now. The drawing always has been of the typical bird of our title, which Caesius adopted in his ParadisaeusAles; but it sometimes is AvisIndica, the Indian Bird.

{Page 44} The planisphere in Gore’s English edition of Flammarlon’s AstronomicPopulaire has the constellation as the HouseSwallow, probably taken from early ornithological lists or the lexicons; for our AndrewsFreund translates Apus as the Black Martin, the English synonym of the Hirundoapus of Linnaeus, — the Cypselusapus of William Yarrell, — not a swallow, however, but a well-known swift of the Old World, with perfectly formed, although small, legs and feet, yet appropriate enough to its mode of life; and the stellar bird appears in Willis’ ScholarofThebetBenKhorat as

Hirundo with its little company;

And white-brow’d Vesta lamping on her path

Lonely and planet-calm;

with this explanatory note: An Arabic constellation placed instead of the Piscis Australis, because the swallow arrives in Arabia about the time of the heliacal rising of the Fishes (Pisces). I have not met with these hirundine star-titles except in these two instances, and think them both incorrect. Mr. Willis’ idea may have come from the Khelidonias (the martin: “kind of swallow-like bird”, Chelidon urbica) of the zodiacal pair (Pisces), but he errs in ascribing the figure to Arabia and in considering it a substitute for the Southern Fish (Piscis Australis), as well as in confusing it with the older Pisces (Pisces).

But all this poem is beautiful in stellar allusions. Here is another bit:

Where has the Pleiad gone ?

Where have all missing stars found light and home?

Who bids the Stella Mira (Polaris) go and come ?

Why sits the Pole-star lone?

And why, like banded sisters, through the air

Go in bright troops the constellations fair ?

Apus similarly appears in China as Cho, the Curious Sparrow; and as the LittleWonderBird. Schiller included it with the Chamaeleon and the Southern Fly (Musca) in his biblical Eve. Gould details sixty-seven naked-eye stars in Apus, its lucida, – gamma, being 3.9. It culminates about the middle of July, but of course is invisible from northern latitudes.

This is one of the twelve new southern constellations with which Bayer’s name generally is associated, although he only adopted them and, Gould says, took them from one of the globes of Jacob, or Arnold, Florent van Langren; but Bayer distinctly attributed their formation to “Americus Vesputius, Andreas Corsalius, Petrus Medinensis and Petrus Theodorus, “navigators of the early part of the 16th century, giving to the last most of the credit of their publication; and Smyth ascribed their invention to “Peter Theodore,” {Page 45} and their publication to another sailor, Andrea Corsali, in 1516. In Chilmead’s Treatise they are indefinitely ascribed to “the Portugals, Hollanders, and English seafaringmen.”

Willem Jansson Blaeu, the celebrated globe-maker of Amsterdam, Chilmead’s contemporary, credited their introduction to Friedrich Houtmann, who observed from the island of Sumatra; while the latter, Semler asserted, took his ideas from the Chinese. Although Ideler denied this, yet he acknowledged that the latter nation knew Phoenix, Indus, and Apus as the Fire Bird, the Persian and the Little Wonder Bird, almost exact translations of the Western titles; and summed up his account of them with the opinion that their origin “is involved in an obscurity that it is scarcely possible to penetrate.”

Star Names: Their Lore and Meaning, Richard H. Allen, 1889.]